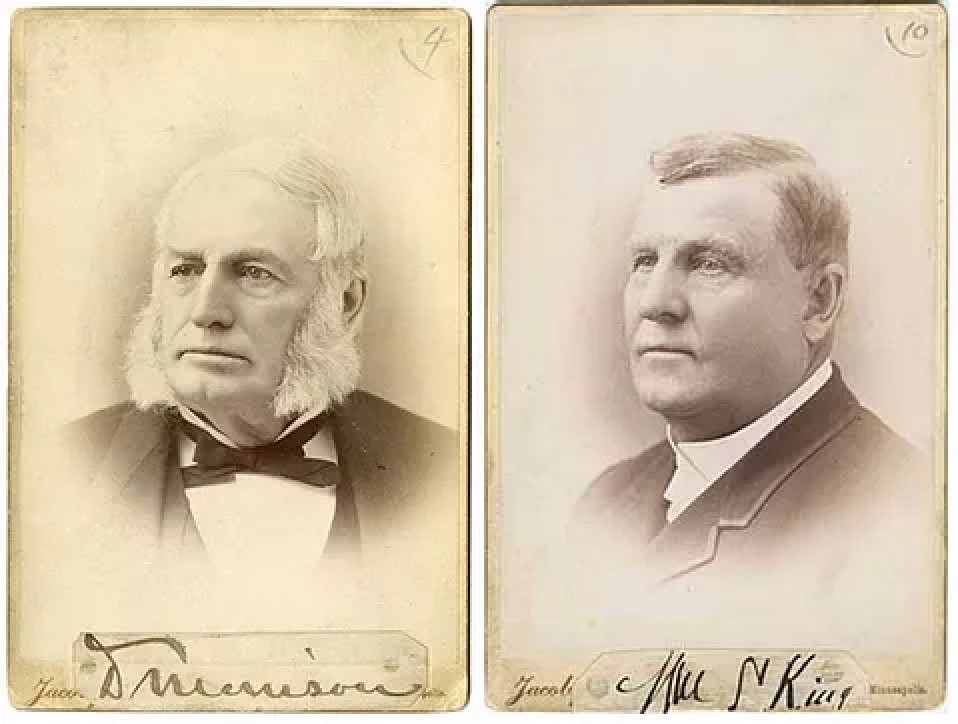

In a previous blog post, “Lakewood and the Park Board: An Entwined History,” we shared the early connections between Lakewood and the Minneapolis Park Board. Lakewood predated the Minneapolis park system by 12 years, making it one of the first park-like spaces in early Minneapolis, and many of the people who helped shape the park system by serving on the Park Board also served on Lakewood’s governing Board of Trustees.

While we may think of the parks primarily as spaces for walking, swimming and gathering in the summer, the Park Board also has a long history of encouraging winter adventure. The story of winter fun in Minneapolis is filled with the names of city leaders and park commissioners now memorialized at Lakewood.

Fun for the PeopleIn the late 1800s, Minneapolis was booming. Milling, logging and factory work turned Minneapolis into a thriving city. Young people moved in from all over the region. They had jobs, paychecks — and many had free time. They wanted a diversion from the doldrums of factory work.

Fairs, fireworks displays and public beaches emerged. And at the end of the summer season, when the fairs and beaches shut down, people didn’t want the fun to end.

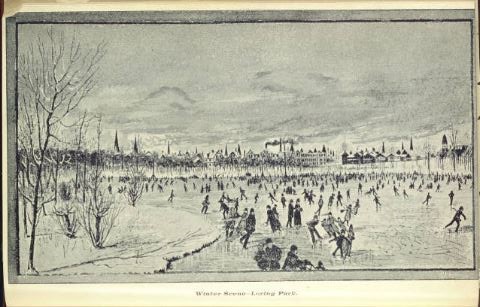

An 1891 drawing of skaters at Loring Park.

Source: Park Commissioners’ meeting minutes

So the Park Board stepped up to support the city’s desire for outdoor activity through the winter. They built sledding hills, ski jumps and skating rinks — and turned the city into a beautiful, winter wonderland.

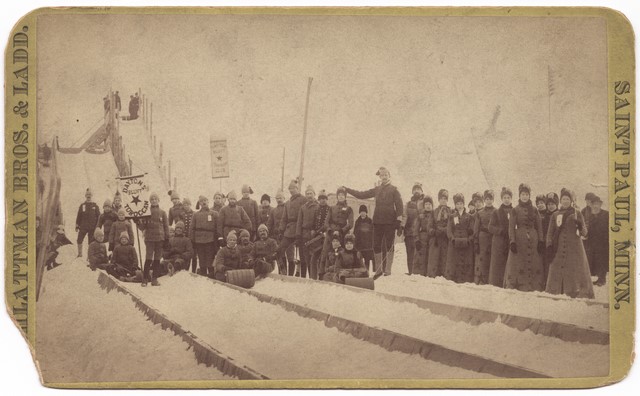

TobogganingAs one late 1800s newspaper described it, tobogganing was a “craze.” Tobogganing clubs, complete with team names and wool uniforms for men and women, sprung up all over the state. Across the Twin Cities, teams would build huge toboggan runs in parks and undeveloped areas, and spend their evenings shooting down the icy slides on sleds. Teams would compete in different towns, or at the annual St. Paul Winter Carnival. They even had a special trolley service that transported club members to and from the slide each night. People of all backgrounds created tobogganing clubs through neighborhood, business or professional organizations, such as the Dayton’s Bluff Tobogganing Club and the Post Office Club pictured below.

The Post Office Toboggan Club in 1886.

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

The Dayton’s Bluff Tobogganing Club in 1886.

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Though the Park Board didn’t immediately jump at the idea of a toboggan chute — after all, it was dangerous — by 1912, they did build a toboggan slide on the south side of Lake Harriet. After a few years, however, the Park Board appears to have closed down the chute but did continue to sponsor the tamer, yet still fun, sledding hills we know today.

The Lake Harriet toboggan slide in 1914, from top and bottom.

Source: Minneapolis Park History

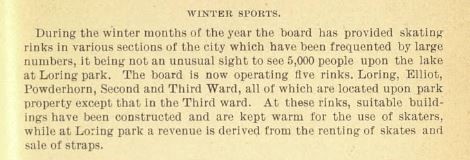

Speed SkatingFor nearly 130 years, the Park Board has provided ice skating rinks for the public. In the late 1800s, Minneapolis residents (especially Scandinavians) were asking the Park Board to create a place for them to skate.

In 1891, the Park Board, under the guidance of Park Commissioner Andrew C. Haugan (buried in Lakewood’s Section 40), built the city’s first public ice rink at Van Cleve Park. Van Cleve Park is named after early Minneapolis pioneers Horatio and Charlotte Ouisconsin Van Cleve: Horatio was a Civil War general for the Union, and Charlotte was an advocate for women’s suffrage and the first woman elected to the Minneapolis School Board. (The Van Cleves are buried in Lakewood’s Section 10.)

A 1901 Park Board meeting pamphlet says they operated five rinks at the time. Source: Park Commissioners’ meeting minutes

The Park Board added more skating rinks, including a large one in Loring Park (shown earlier in the article). But the rink that would gain international renown was in South Minneapolis’s Powderhorn Park.

In 1930, with the support of the Park Board, Powderhorn’s pond became a world-class speed skating rink. It held national and international competitions and was a popular training facility. At the time, the Park Board included Lakewood resident Maude D. Armatage, who was the first woman on the park board and the member with the longest consecutive terms. (Armatage is buried in Section 14 at Lakewood.)

The rink at Powderhorn in 1934.

Source: Historyapolis

Powderhorn skaters.

Source: Historyapolis

Ski JumpingAnother activity that the early immigrant Scandinavians brought with them to Minnesota was ski jumping. Daring skiers would plunge down a 90-foot slide only to be launched into the air, covering huge distances and reaching new heights with just their skis to ease their landing.

In 1909, the Park Board expanded North Minneapolis’s Glenwood Park to acquire neighboring land on which a group called the “Twin City Ski Club” had already built a private ski jump. At first, the ski jump was a huge hit with the media. Newspapers as far away as Tacoma, Washington and Albuquerque, New Mexico covered the death-defying feats of the jumpers.

A 1909 article from the Tacoma Times.

Source: Library of Congress.

Despite all the media attention, the intrigue of ski jumping proved to be a series of false starts, and the sport never gained much traction here. Though it appears that a ski jump may have existed in Glenwood Park for another decade or so, coverage of the activity dropped off in newspapers and Park Board reports.

In the late 1930s, after the Great Depression had turned the affordable activity of speed skating into the winter sport of choice, the park was renamed Theodore Wirth Park. Former Park Commissioner Theodore Wirth was largely responsible for designing the Minneapolis park system. (Wirth is buried in Lakewood’s Section 25.) Today Wirth Park is home to some of the city’s most popular cross-country ski trails.

An Enduring LegacyThe Minneapolis park system, now called the Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board, is consistently ranked the best in the country. Designed for year-round fun (by many people who are now laid to rest at Lakewood Cemetery), the parks continue to provide outdoor activities in every season. Today the Park Board also offers ice fishing, tubing and snowshoeing. It operates two dozen ice rinks and more than 20 miles of groomed trails. It also puts on the annual Lake Harriet Winter Kite Festival that Lakewood helps sponsor, taking place on January 25, 2020.

In contrast, Lakewood offers a quiet, reflective space in the winter, with over nine miles of roads on which walkers and drivers alike can experience a peaceful escape from the excitement. On a visit (our gates our open to the public 365 days a year), you’ll find winter wildlife, expansive views, beautiful monuments, fresh holiday wreaths and evidence of our rich and diverse local history.

Special thanks to David C. Smith for his research on the history of Minneapolis parks.