On June 14th we celebrated Flag Day to honor our nation’s adoption the official United States flag. This holiday got us thinking about the origins of our own state flag. So today we look at the history and artistry of the Minnesota state flag–and its connection to Lakewood.

In 2001, the North American Vexillological Society (vexillology is the study of flags) ranked Minnesota’s flag as one of the ten worst flag designs in the U.S. and Canada. According to the survey, the flag has too many symbols and too much information to be understood at a distance. This contest did not even take into account historical and political accuracy, which has also been grounds for critique and change of the state’s flag. But the flag’s intricacies and inaccuracies, while not making for the most “effective” flag, hold a wealth of artistic and social history.

35 Years Without a Flag

It was Friday, October 13th, 1893. The 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago–which saw 27 million attendees, the construction of nearly 200 new buildings, the world’s first Ferris Wheel, exhibits from 47 different nations and much more–was nearing the end of its six month run. But today was a special day. It was Minnesota Day! 20,000 Minnesotans came down to the Windy City to march through the streets and celebrate our state’s accomplishments. Fair officials noted that Minnesota Day was among the best attended and most celebratory days of the Fair.

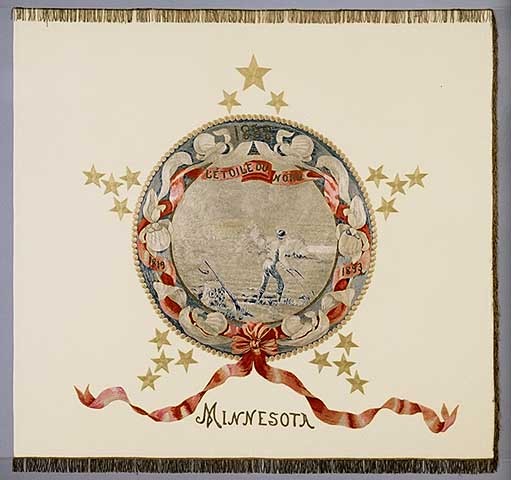

On proud display that day was the brand new Minnesota state flag. But the flag had made a splash at the Fair long before Minnesota Day. Displayed in the Women’s Building, which celebrated the accomplishments of the nation’s women artists, the Minnesota state flag won a gold medal for its flawless embroidery.

Minnesota had been a state for 35 years before the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. However, our state had no flag a mere eight months before the Fair. So, how did we go from having no flag to boasting an award-winning flag in a matter of months?

The process actually began a couple years prior. After Chicago was announced as the location for the 1893 World’s Fair, the 1891 Minnesota legislature passed a resolution to sponsor an exhibit to showcase Minnesota’s artistic and industrial feats. By 1892, a “Women’s Auxiliary Board” was formed to take on much of the planning for Minnesota’s presence at the World’s Fair. Within this group of women, a six-person state flag committee solicited submissions and selected a design for a flag–a banner under which all of the state’s accomplishments would be celebrated.

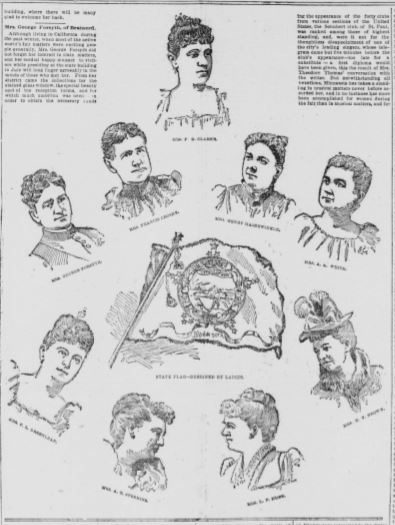

A St. Paul Daily Globe article from 1893 celebrated the accomplishments of the Women’s Board, which included the collaborative creation of the state flag. Source: St. Paul Daily Globe (via Library of Congress)

On the last day of February in 1893 (just two months and one day before the beginning of the Fair), the board selected the winning design out of nearly 200 submissions. The design was submitted by local artist Amelia Hyde Center. Center, who later relocated to Chicago to successfully pursue art and leatherworking, was a student of Minneapolis’s early art movement. A 1904 Minneapolis Journal article even said that Center was “regarded as the founder of the Minneapolis arts and crafts movement.” Amelia Hyde Center, who is laid to rest in Lakewood’s Section 6, was paid $15 for her design.

History and Symbolism

The 1893 flag may have been the first official flag of Minnesota, but unofficial flags had been flown previously. During the Civil War, for example, it was customary for some Union Army regiments to carry blue flags with their state seal in the middle. Minnesota had adopted a state seal in 1861; the 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 5th Minnesota regiments carried such a flag. Amelia Hyde Center’s design was likely based on these Civil War-era flags. In Center’s 1893 design, the state seal was the centerpiece of each side of the flag, with a blue backdrop on one side and a white backdrop on the other.

Both the state seal and Center’s artistic additions were loaded with symbolism. Within the state seal, three pines represented both the state tree and the state’s three great pine regions of the St. Croix, Mississippi, and Lake Superior. The image was surrounded by 19 stars, representing Minnesota as the 19th state admitted to the Union. Pink and white lady slippers–the state flower of Minnesota–surrounded the seal. The seal also featured the state’s motto, “L’Étoile du Nord” (the Star of the North) within a decorative ribbon. Center included three dates on the f: 1819 (the year Fort Snelling was established), 1858 (the year of statehood), and 1893 (the year the flag was adopted). The state seal depicted both a white settler and a Native American man. These depictions would later draw controversy as being historically inaccurate and offensive. The settler plowed a field alongside a stump (representing the agriculture and logging). Meanwhile, the Native man rode away from the settler, implying, falsely, that the Native population voluntary “left” to make way for settlers. The state seal was later changed to address this historical inaccuracy (see “Artistry and History Demand a New Flag”).

Making the First Flag

The historically-inaccurate, perhaps overcrowded design of the original 1893 flag may have made for an unfavorable flag. It did, however, give a pair of Minnesotan embroidery artists a lot to work with. Those artists were sisters Pauline and Thomane Fjelde. The Fjeldes emigrated to Minneapolis in the 1880s from a small fishing village in Norway. Here they joined their brother Jakob, a sculptor who arrived in Minneapolis a few years prior. Together Pauline and Thomane opened a dressmaking and embroidery business, through which they served many of Minneapolis’ wealthy elite. Having made a name for themselves as masterful needleworkers and embroiderers, they were commissioned to sew the new official state flag.

The intricate flag was embroidered masterfully by the Fjelde sisters. In addition to the double-sided flag featuring the state seal, banners, flowers, stars, and dates, the Fjelde sisters also sewed beautiful gold fringe along the flag’s border. Their work earned them a gold medal for embroidery at the World’s Fair.

The original state flag, embroidered by Pauline and Thomane Fjelde. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Pauline and Thomane weren’t the only Fjeldes to display works at the World’s Fair. Jakob, whose works include celebrated monuments like Loring Park’s Ole Bull statue and Central Library’s “Minerva,” had the honor of displaying his newly-completed sculpture of Minnehaha and Hiawatha–which is still featured in Minnehaha Park–outside the main entrance to the Minnesota exhibit. The artistic Fjelde family is buried at Lakewood in Section 11. Robert Koehler, another artist now buried at Lakewood, also displayed three pieces at the Fair, including his now-famous work “The Strike.”

The Fjelde family grave at Lakewood in the 1920s. Source: Minnesota Digital Reflections

Artistry and History Demand a New Flag

Ultimately, the Fjelde sister’s masterful embroidery of the flag’s intricacies made the flag too difficult to reproduce on a mass scale. In 1957, a minor but significant change was made to simplify the design of the flag: the flag became single-sided with a blue background. The opposite side of the flag was simply a reversed image of the front of the flag, rather than featuring the state seal on a white background.

But it hasn’t just been artistic complexity that has led to changes in our flag overtime. The Civil Rights era of the 1960s offered a platform for critiques of the state seal, and thus the state flag. As mentioned above, the seal’s imagery controversially suggested that Native Americans in what became Minnesota voluntarily “left” when settlers arrived. In 1968, the Minnesota Human Rights Commission asked the state government to design a seal that Minnesotans, Native and non-Native, could feel proud of. New seals were designed throughout the 1970s, and in 1983, the seal (as well as the flag) was subtly modified to reposition the Native rider as riding slightly toward settler, rather than riding away. This change was intended to acknowledge Native Americans’ role in early Minnesota, and reverse the implication that the Native populations “left.”

Though many considered this change to be a step toward historical accuracy, many also feel that the changes did not go far enough. The history of Minnesota is complex–too complex to fit onto a small flag. Many Minnesotans today carry on the conversation about how to create a flag that is both honest and beautiful.